3 St. James Park

PLEASE SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

BERKELEY SQUARE WILSHIRE BOULEVARD FREMONT PLACE

WINDSOR SQUARE WESTMORELAND PLACE

FOR AN INTRODUCTION TO ST. JAMES PARK, CLICK HERE

PLEASE SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

BERKELEY SQUARE WILSHIRE BOULEVARD FREMONT PLACE

WINDSOR SQUARE WESTMORELAND PLACE

FOR AN INTRODUCTION TO ST. JAMES PARK, CLICK HERE

IT SEEMS THAT ONLY THEIR FAMILY might have clear photographs of the Eugene Payson Clarks—perhaps one that might even contain a smile. Unlike some of their social peers, the Clarks appear to have adhered closely to the old dictum that one's picture must not be seen in the press more than once or twice during one's lifetime. There might be a newspaper announcement of one's birth, but only a trashy Hollywood movie star would include a picture of one's baby. An engagement or wedding portrait was acceptable, as was, if the newspaper editor deemed one important enough, a dignified shot to illustrate one's obituary. Occasionally one of your more exhibitionist fellow matrons might allow a Times photographer into a party, allowing him to snap away despite one's narrowed eyes—such seems to have been the case in Constance Clark's glare below at the 1959 Assembly Ball. Similarly, her husband, dutiful heir to his father Eli P. Clark's real estate interests, seems never to have been caught smiling in public.

|

| Constance and Eugene Clark |

Interestingly, the very house the Clarks built at 3 St. James Park in 1916 has shown every sign of photographic reticence. This, despite its design having been attributed to the eminent Arthur Rolland Kelly, who had been employed by the equally formidable Letts and Janss families. There have been a few tantalizing bits of description of the Eugene Clark house; its motif seems to have been Colonial. It was one of the last houses, if not the last, to have been built in St. James Park, and it may have been a wedding present from Eugene's parents. Its lot was one house from West 23rd Street, about 120 feet north of the parental domain at #9. Though there was a third Clark family household in later years designated #7—possibly a separate structure but more likely a duplexing of #9—the space between the homes of father and son appears to have been a private park for Clark children and grandchildren and one in which family celebrations were held.

|

| Eugene Clark had merely to stroll to the corner of St. James and West 23rd Street— just beyond the streetcar above—to catch the Los Angeles Railway's U line to his office downtown. |

Even if it wasn't proper while sitting for a studio portrait to mark the occasion, one hopes that Constance Byrne deigned to smile on her wedding day. She should have been beaming, capturing as she had a major prize of the neighborhood. Her father, Canadian John J. Byrne, an assistant passenger traffic manager with the Santa Fe Railway, might have been more familiar with the Cheaps of 12 St. James Park—Albert Cheap being also a Santa Fe man—than with the Clarks of #9. Certainly the Byrnes were nowhere near as rich as the Clarks. This is not to say that the Byrnes were from the wrong side of the tracks; they had been living in West Adams since their arrival in Los Angeles in the early '90s. After a decade at 2624 South Figueroa, the Byrnes moved around the corner to 630 West 28th Street, both houses in prime West Adams and very near St. James Park. The self-made John J. Byrne had arrived, and now his daughter had hit the jackpot.

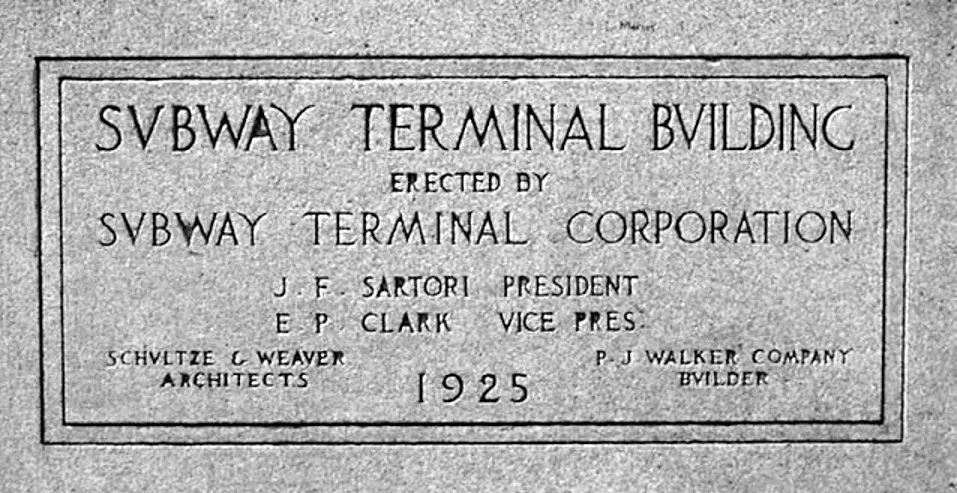

The Byrne-Clark nuptials took place on May 29, 1916; while 300 guests were in attendance at St. John's, the establishment Episcopal church just around the corner from the Byrne house, there was no reception due to the illness of the mother of the bride. The newlyweds set off on a summerlong honeymoon; their new house at #3 was under construction and they expected to move in by September 15. Constance Jr. arrived on August 27 of the next year; Joan turned up on May 20, 1920. The extended Clark family's near acre on St. James Park would provide the backdrop for a lush life for decades to come. Of course, we're talking about a lush life in a grand bourgeois style, one without the gaudy excess and scandal of Hollywood that was beginning to symbolize Los Angeles in the '20s and that would draw still more new residents to the city. The usual genteel parties favored by the Clarks' Los Angeles brethren took place with regularity in both family houses and in the garden between them. The senior Clarks at #9—Eli and Lucy and Eugene's maiden sister Lucy Jr.—were able to enjoy watching Constance Jr. and Joan grow up next door. On weekday mornings Eli would walk up to meet Eugene in front of #3 and the two would catch a U line Yellow Car at the corner of 23rd Street to go to their offices downtown; once Eugene and Constance were settled on the Park, much of father and son's energy went into planning their crown jewel, the Subway Terminal Building, which would open in 1925 across from the family's Hotel Clark on Hill Street. It was not, however, all work for the boys. There were family trips to Europe and Mexico and to Hawaii, a common destination of prosperous Californians, on the City of Los Angeles in the '20s, and on the Lurline and Mariposa in the '30s.

|

| The "E P Clark" engraved on the cornerstone above refers to Eli P. Clark rather than his son, Eugene P. Clark. After his father's death in 1931, Eugene became president of the Subway Terminal Building; he was also president of the Clark and Sherman Land Company, the Del Rey Company, the Main Street Company, and the Building Owners' and Managers' Association. His vice-presidencies included those of the Capitol Crude Oil Company and the Eli P. Clark Company. He was part owner of the Hotel Clark on Hill Street and the Central Building. |

Eugene and Constance's daughters were young ladies whose self-expression would be confined to the proprieties of the right schools, to the dainty rituals of subdeb- and debutantdom designed to preserve the complementary auras of virginity and male prerogative, and to matronly Junior League smartness. The girls attended Marlborough, the school for proper young ladies that had until 1916 been practically in the Clarks' backyard at 23rd and Scarff but was now (and still is) at Rossmore and Third. Later, Constance was sent east for a time to Ethel Walker's; she was graduated from the Katharine Branson School in Marin County before going east once again, this time to matriculate at the Garland School of Homemaking in Boston, where, presumably, the art of laundering little white gloves was included in the curriculum. Joan was apparently disinclined to venture far from Los Angeles, moving from Marlborough to the Carl Curtis School before attending Pomona College. While the Clarks were quietly very rich, if not as rich as other unrelated Los Angeles Clarks in the neighborhood, they seem to have been quite content in their provincial bubble. The family compound remained intact after the death of patriarch Eli in 1931, with the Lucys remaining at #9 and Eugene, Constance, and the girls at #3. A record of Arthur Rolland Kelly's projects indicates that he was recalled to #3 in 1934 for remodeling. The "Beau Peep Whispers" column of the Times described this as being done "to accommodate the family comfortably and artistically," though future family debuts and weddings were perhaps also being considered. Constance Jr. was feted in these ways in due course, and the ritual showcasing of maidens worked in her case: By the spring of 1940 she was engaged to proper Pasadenan John Laurie Martin, three years her senior, a descendant of old New York families and a graduate of Stanford and Harvard Law. The wedding was on September 18 in the family garden, with the bride presented virginally in something arcane called marquisette and finger-tip tulle. Joan was her sister's only attendant; the Reverend George Davidson of St. John's officiated. Thirteen months later son and heir Eugene Clark Martin arrived. Buttons busted from West Adams to Pasadena.

|

| Smiles seem to have been doled out sparingly in the Clark family: Constance Anne Clark's formal wedding portrait appeared in the Los Angeles Times on September 19, 1940. |

The next family wedding was a low-key wartime affair in the chapel of St. John's on February 15, 1943, in which Joan married Trude Clark Taylor, who'd grown up in Bear River City, Utah, and attended Utah State. He was in Los Angeles working for Northrop; after his service in the Pacific theater he would receive an engineering degree from UCLA and an MBA from Harvard, followed by a long and distinguished career in the electronics and computer industries—a man of whom both Eli and Eugene would have been extremely proud. Joan and Trude lived in the Pasadena area for most of their lives; they had three children and 63 years together before she died on August 16, 2006; Trude followed on February 21, 2008.

Constance and John Martin had a rockier road of matrimony. After his war service, the couple resumed married life and had a daughter, Mary. They also increased the Clark presence on St. James Park by moving into #3 with Eugene and Constance. The house was further remodeled to incorporate a separate residence for the Martins: Telephone directories and social lists into the '50s gave this new St. James Park address as #3½. Southfork living is not for everyone, and it can be especially tedious for in-laws. The Times's latest social-gossip diva James Copp began to report odd bits regarding John Martin, whom he seems not to have liked, in his "Skylarking" column, including mentions of the petroleum lawyer laughing at his own jokes. In late 1953 Copp quoted Martin on his definition of marriage: "It's that point in time when the neuroses of two neurotics are in harmony." With that kind of harmony it is perhaps not surprising that the Martins were kaput by the next year. By 1955 they had moved out of #3½ and were living apart though not far from one another, perhaps for the sake of the children, in the Westlake district. John remarried in short order—one imagines his ex-mother-in-law's raised eyebrows—but he died suddenly in Washington, D.C., on December 28, 1957. Despite the divorce, his death was no doubt difficult, at least for his children, coming as it was on the heels of Eugene's fatal heart attack six months before—he'd died at home at #3 on June 27. The Clark presence on St. James Park, already having lasted well past the prime of West Adams, was drawing to a close.

Eugene had succeeded his father as a director of the Citizen's National Bank in 1931, though this was only a small part of his business life that included running the family interests in oil and real estate. His other directorships at the time of his death included those of the local Red Cross chapter and the Los Angeles Metropolitan Traffic Association, as well as of Rosedale Cemetery—though he would be buried, as were all Clarks, at Forest Lawn. A tribesman down the line, he was a member of the California and Bohemian clubs, to name just two. Constance Sr. was still listed at #3 in the 1963 Southwest Blue Book, published in late 1962, but nearly 60 years of Clarks on St. James Park were ending. After a long illness, she died in Los Angeles on December 11, 1969.

Constance Jr. married William D. Blanford in 1959 and later lived in Pacific Palisades. Despite neither side of her family having been in Los Angeles in its first hundred years, she seems to have always been fond of the ancestor-worshipping First Century Families, at whose luncheons she romanticized forebears with several other St. James Park members including Dockweilers and Meylers; she went off to Clark Valhalla herself on July 2, 2004.

Number 3 St. James Park had some life left in her yet: From 1964 to 1969, the Reverend J. A. Francis was in residence. The house was listed in the July 1973 city directory as the Christ the King Center. But soon, #3, now 50 years old, would give way to asphalt. Two mature palms remain to mark its front walk.

|

| Two palms remain to mark the site of 3 St. James Park |

Illustrations: proquest.com; LAT 1, 5; Tom Wetzel 2;

Images of America: West Adams 3; PhotoJenInc 4;

Art of The Luggage Label 6; Google Street View 7