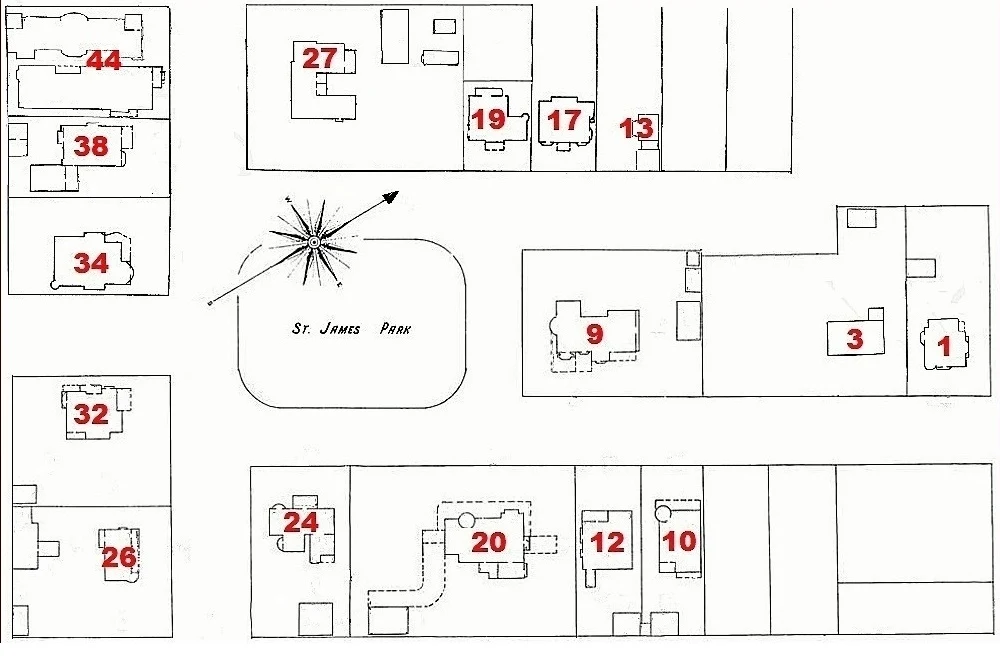

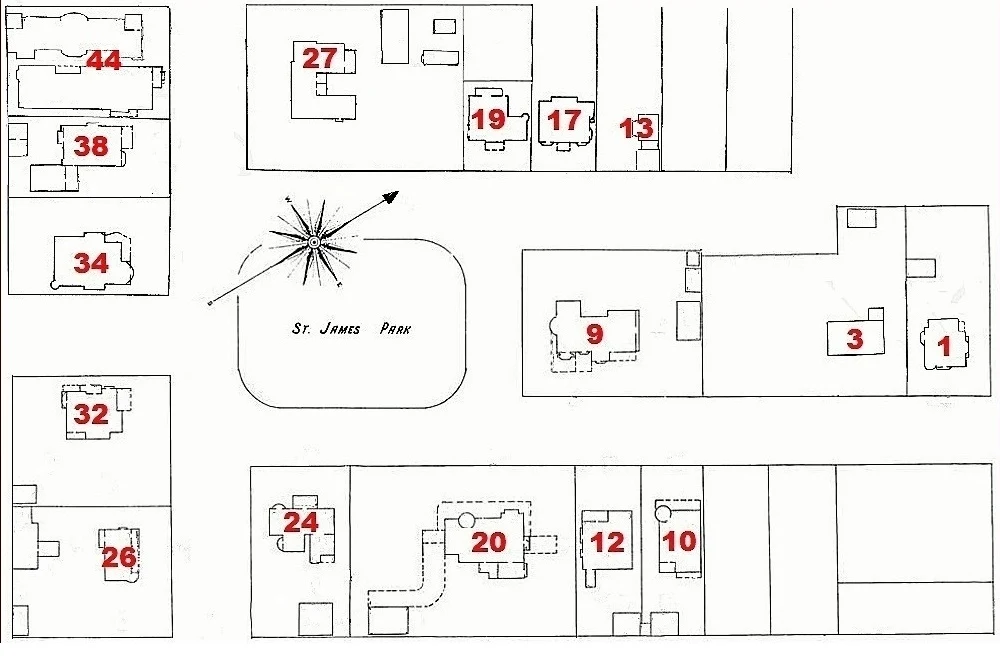

1 St. James Park

PLEASE SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

BERKELEY SQUARE WILSHIRE BOULEVARD FREMONT PLACE

WINDSOR SQUARE WESTMORELAND PLACE

PLEASE SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

BERKELEY SQUARE WILSHIRE BOULEVARD FREMONT PLACE

WINDSOR SQUARE WESTMORELAND PLACE

FOR AN INTRODUCTION TO ST. JAMES PARK, CLICK HERE

As would many of the lots that would constitute St. James Park in its maturity, that of #1 remained empty for many years after Messrs. King, Harvey, and Harkness established their subdivision in 1887. While in the long run the men would prosper, their timing in laying out West Adams's most exclusive district was not good—within months, the Los Angeles housing boom spurred by the competition of the transcontinental railroads into the city had gone bust. There was relatively little real estate activity through the '90s as bust gave way to the Panic of 1893. Once conditions improved, lots once again moved, resulting in some impressive dwellings surrounding the Park once the new century came. Richard Mercer, noted in various records as a "capitalist"—that Gilded Age mark of honor—was himself prospering by the end of the '90s; he built our subject house on the prominent southwest corner of West 23rd Street and Park Grove Avenue in 1899.

Number 1 St. James Park, pictures of which remain elusive, only came by its address after it was built. While #9 was originally addressed 2327 Park Grove Avenue, that house lay on lots 27 and 28 within the bounds of the original St. James Park tract; #1, on a lot measuring 75 by 169 feet at the southwest corner of West 23rd and Park Grove was, like the lot of #3 built in 1916, part of the Ellis Tract Annex, whose parent lay just to the west and north. What did not come down in scale after the financial troubles of the '90s in terms of the houses of St. James Park was the original developers' hopes for a neighborhood of particular éclat: Even in its early sparseness and even prior to neighboring Chester Place's opening, a St. James Park address denoted one's having arrived. The developers of other tracts nearby were not shy about advertising their properties as being in the St. James Park neighborhood; eventually, at least two houses originally without Park addresses, #9 and #1, would change designations to feel the love. Within two years of completion, 2305 Park Grove Avenue became 1 St. James Park.

Foreshadowing a drift that would continue until the Pacific prevented Los Angeles from extending any farther, the center of gravity of the city's West Adams district would slide westward from Main Street after the turn of the century. Many families who once lived east of Figueroa would seek newer, less dense surroundings. St. James Park was part of what was being called West Los Angeles, a suburban district whose name was passed on in later years and supplanted by "West Adams" after its central, and finest, residential thoroughfare. The Richard Mercers were, as such early L.A. residencies went, practically old Angelenos, having come from the Nevada gold fields in 1883, with, presumably, a pile. Mercer first appeared in city directories in 1884, living at 147 South Olive Street. He moved south seven blocks within a few years, and then another five squares below that to 314 West Pico Street by the '90s.

|

| While Richard Mercer wasn't one of the famed Silver Kings, his success alongside them in the Nevada fields would afford he and his wife a top-drawer life in his adopted city of Los Angeles. |

Richard Mercer was born in England in 1838. He appears to have come to America 17 years later, was naturalized in 1864, and eventually sought his fortune in them thar hills of the Comstock Lode. It is not entirely clear what his interests in actual mining were, but, of course, the actual treasure was not the only way to riches in the boomtown of Gold Hill, Nevada. To hedge his bets, Mercer became a major supplier there of groceries and provisions, wines and liquors, crockery and glassware and other house furnishings. His strategy of covering the bases in case he didn't strike it rich underground paid off: Richard Mercer would arrive in Los Angeles not as a miner or merchant but as a holder of the butchest occupational title a man could have in late-19th-century urban America: capitalist. In November 1869 he had married Mabel Louise Vanfossen in Gold Hill; she'd found her way to Nevada from California or Virginia, depending on the census year and enumerator. The couple had three children, none of whom survived childhood. Sad as this might have been, it appears to have left the Mercers ample time to pursue a vigorous social life: Over the next 25 years, they would prove themselves indefatigable partygivers and -goers, with dozens and dozens of appearances in the social columns of the Times and the Herald. Richard Mercer became a real estate investor in Los Angeles and helped start the Western Lumber Company in 1888; with his fortune made before arriving, he did not seek to become a builder of the city in quite the vein of, say, Eli P. Clark, whom he counted as a friend and neighbor. But the Mercers were certainly accepted into the higher reaches of local capital-S Society. Throughout the '90s they were frequently counted at parties with the likes of the I. N. Van Nuyses, the William May Garlands, and the Walter Lindleys, as well as among the biggest names of St. James Park, Chester Place, and Adams Street—the Walter Newhalls, the Eli and the J. Ross Clarks, the Richard Days, and the William Hayes Perrys and Charles Modini-Woodses. Augusts were spent with many of these major L.A. players at the Metropole on Catalina. No doubt Mercer's friendships among them alerted him to the charms of St. James Park. Louise would certainly have heard about the subdivision's late-'90s revival at the many card parties she was part of—judging by the breathless reports of her social activities in the papers, the girl certainly seems always to have been up for the chance to shout "Gin!"...or whatever one shouts when triumphant at euchre or whist, games of fashion circa 1900. In 1898 the Mercers left Pico Street, an area becoming increasingly commercial, and took up residence at the Hotel Lincoln on Hill Street while they contemplated their next move. Before long, the couple purchased Lot G in the Ellis Tract Annex. While technically not part of the original St. James Park tract, it was within one of its city squares and within a few hundred feet of the park itself. Lot G was certainly poised to bask in the revived cachet of the 1887 development, which may have mitigated its perhaps not being the quietest lot the Mercers could have chosen. The Los Angeles Railway's University line ran along 23rd Street, and the Marlborough School for Girls was immediately to its west at 865 West 23rd on the Ellis Tract Annex's Lot A. (The school had been housed in the old Marlborough Hotel—from which it derived its name—since 1889, and would remain on the southeast corner of 23rd and Scarff until 1916, when it moved to Rossmore and Third, where it still is today.)

The Los Angeles Herald of September 29, 1899, reported that "Mrs. Mabel L. Mercer" had just let a $3,000 contract for a two-story, 8-room frame residence on the "south side of 23rd Street, near Park Grove Avenue." Even in a time when women couldn't vote, it was not uncommon for a well-off couple to put a house in the wife's name or for her to maintain separate funds. The new house was completed by the spring of 1900, and the entertainments began almost immediately. More whist, more euchre, more hobnobbing with le toute-Los Angeles, who'd made the West Adams Street corridor its new domain.

Perhaps the grinding of the Yellow Cars along 23rd Street and the screeching of the young ladies next door did finally prove to be too much for the Mercers; or perhaps Richard, still active in business despite nearing 70, hadn't lost his sense of when to buy and when to sell. At any rate, the Times reported on March 21, 1906, that, in exchange for $11,000, the Mercers had recently sold 1 St. James Park to a doctor newly arrived in Los Angeles from Ohio. Richard and Louise moved to Colegrove—now the southern part of Hollywood—to contemplate their next move. This came two years later when the Herald reported on August 23, 1908, that a permit had been issued for a two-story, eight-room, $5,200 house—no smaller than #1—to be built at 987 South Manhattan Place in the new Country Club Heights tract 2½ miles northwest of St. James Park. Still active in real estate even in his 70s, it seems that Mercer may have built houses on spec, occupying them himself until he found a buyer. After living on Manhattan Place for less than a year, he and Louise moved to the Fremont Hotel on Bunker Hill. Mercer helped capitalize a new firm, the Huber Realty Company, in 1910; by 1912 he and his wife were living in a new house back in Country Club Heights at 1001 South Gramercy Place. This time they stayed put for a while—at least until 1921. The exact dates of the Mercers' deaths remain elusive, but both were definitely dead by October 1925 when the widow Louise's will was being contested by a niece.

§ § § § § § § § § §

|

| Dr. Charles Price Wagar |

When a house is remembered by its name, it is usually by that of its longest-term or most interesting tenants, who take precedence even over the builder. By rights on both counts, then, 1 St. James Park should be called the Wagar house. Dr. Charles Price Wagar was born in Cleveland on September 23, 1852, and spent the first 53 years of his life in his home state. In adulthood he pursued advertising and then journalism, establishing Wagar's Official Railway Guide in 1881. After marrying Theresa Marie Obermiller of Tiffin, Ohio, in 1883, perhaps at her urging, he entered the Northwestern Ohio Medical College, becoming prominent in short order in his new field of allopathy. Settling in Toledo, he managed to combine medicine with his love of words by continuing his railway guide and adding The Medical and Surgical Reporter: A Monthly Journal to his publishing efforts.

Theresa Wagar came from a most interesting family. Her father, Johann Meinrad Obermiller, emigrated from Austria in 1848 and opened a medical practice in Seneca County, Ohio. Theresa's younger sister, Effie Barbara Obermiller, was also a doctor—no doubt father and daughter were inspirations to their new in-law Charles Wagar. Mrs. Obermiller, née Mary Anna Bork, was described as "artistically inclined"; so was the Obermillers' son Philip, who died at 28. Theresa's older sister Marie Louise became a painter of some note. Theresa and Charles Wagar had four children, though only two daughters survived infancy. An unnamed child apparently died at birth; twins Mortimer and Marie Louise were born in 1890, though Mortimer didn't survive the year; Jessie was born in 1893. It is not known why the family decided to leave the bosom of Obermillers and Wagars—it could have been that it was all a little too bosomy, it could have been for reasons of the delicate health of Charles or Jessie or both, or it could have been simply to get away from the slush. But in 1905, the Wagars left for the coast. Their letters of introduction must have been impressive. Not only did the family secure one of the nicest addresses in Los Angeles, but Charles was taken into the uber-poobah California Club forthwith. He also immediately became active in several other organizations where there actually were such things as grand poobahs and robes and secret handshakes, fezes and wizards, strange chants and manufactured claps of thunder. He kept his finger in journalism, taking on the managing editorship of the California Medical and Surgical Reporter. There seems to have been no lengthy initiation period for the new Angeleno, which would turn out to be a good thing: After just two years in Los Angeles, Charles Wagar died on June 6, 1908. He was just 55.

Though she would spend periods of time back in Ohio over the next 36 years, Theresa Wagar and her daughters carried on at #1 after Charles was buried at Rosedale. The Obermiller sisters had been sent to Paris for their educations—Theresa at age 13. The Wagar girls went to school locally at Marlborough, almost literally in their backyard at the time. Marie was graduated in 1907; following Jessie's graduation and a European tour with her Aunt Louise, she later enrolled in the Institute Savaete in Munich. Sadly, and of unknown causes, Jessie died in Los Angeles at age 19 on February 2, 1913. And still Theresa and Marie stayed on at #1. There were trips back to Ohio for family reunions, but apparently, even without extended family nearby, the Wagar ladies chose to remain in Los Angeles. Their cultural pursuits—Theresa was considered a gifted pianist—earned them places in Who's Who Among The Women of California; their listing in the Southwest Blue Book indicates a degree of social popularity among the local bourgeoisie.

In terms of 1 St. James Park itself, change was to come that would be reflective of the growing population density of West Adams. The growth of Los Angeles during the '20s is legendary, with its population well more than doubling during the decade. The effect on aging, close-in neighborhoods such as St. James Park was negative in terms of many of the old houses. An increasing number were demolished and replaced by apartment buildings or themselves cut up into flats, creating a less attractive atmosphere. For property owners, however, this could be a boon. They could sell and then be set for moves to newer, more spacious neighborhoods to the north and west. Some St. James Park homeowners liked their surroundings enough to stay despite the nearby crowding or signs of urban decay exacerbated by the Depression. For a widow it would only be smart to seize the opportunity to capitalize on her real estate, and Theresa Wagar was lucky in that her lot was big enough to allow her to stay in her long-time home and at the same time develop half of it. Whether she sold the western half of her lot or built the apartment house at 845 West 23rd Street is not known, but either way it was apparently worth the loss of her garden to reap the profit or rents.

|

Louisa Obermiller, who came to live with her sister at

1 St. James Park during the 1930s, painted

Modern Peonies while there.

|

Likely it was on a return trip to Ohio that Marie—at 33, seemingly set for spinsterhood—became engaged to 39-year-old grocer Frank Henry Rudd. The Chandler & Rudd Company was an old Cleveland firm that catered to the carriage trade, to which Rudd himself belonged. A particular feather in his cap was that one of his mother's brothers was John D. Rockefeller. Marie had hit the Ohio jackpot—it was Euclid Avenue all the way from now on. Even with her only child now having left Los Angeles, subdividing her property allowed Theresa to keep #1 and spend extended periods back east. She seems to have kept a house or apartment in Cleveland at various points in time, and there were years when she rented out #1, even when in Los Angeles. After Marie married, the house was occupied by Mrs. James Musselman, who was in residence into the early '30s. During that time, when in Los Angeles, Theresa lived in a bungalow at 1262 North Kenmore; later, with her Ohio cousin Marie Bork, she was in Pasadena at 307 North Baldwin Avenue. By 1932 Theresa had returned to #1 on a more permanent basis. After years of study and work abroad, her sister Marie Louise, the now quite accomplished painter known professionally as Louisa Obermiller, came to live at St. James Park. Her painting Modern Peonies, seen just above, was done around this time. Louisa fell ill in the spring of 1940; she died at Queen of The Angels on October 4, 1940, at age 85. Theresa remained at #1 until her own death on January 18, 1944. She was 86. The sisters' remains were sent back to Toledo for burial in the Obermiller tomb.

§ § § § § § § § § §

|

| The prolific writer Eleanor Gates, seen here circa 1912. She died in 1951 after being hit by a car near her home at 1 St. James Park. |

The Wagars had owned 1 St. James Park for nearly 40 years by the time of Theresa's death. How long the house may have remained in the family is not known, but it appears to have once again become a rental property—during the war and after, housing was even scarcer than it had been in the '20s. One tenant in the late '40s was the playwright Eleanor Gates, who'd been living in the neighborhood for some time. Gates had had seven plays produced on Broadway, including an adaptation of her novel The Poor Little Rich Girl; later there were movie versions of it starring Mary Pickford and Shirley Temple. During her long career she produced many other books and newspaper and magazine articles for such publications as The Saturday Evening Post, Cosmopolitan (before its focus on the hooker look), The Delineator, Munsey's, The Century, and The Woman's Home Companion. Her prolific output allowed her to indulge in her passion for horses. She was credited in her Los Angeles Times obituary with having introduced Arabian horses to California; at one time she maintained a large ranch near Los Gatos, later sold to violinist Yehudi Menuhin. The 75-year-old Gates was hard at work on a number of projects when she died on March 7, 1951, after being struck by a car a few days before while alighting from a bus on Adams Boulevard two blocks from home.

§ § § § § § § § § §

Just who might have owned and rented 1 St. James Park after Eleanor Gates's time is unclear. In the mid-'50s, Wiley Hines Lide was in residence; later, James F. Donely. Eventually broken into apartments and from 1961 listed in city directories as "Tremond House," Domingo Aguillen was among those living at #1 until its last directory appearance in July 1965. During the '60s, many Los Angeles neighborhoods that began as suburbs full of impressive houses were emptying of residents who had the resources to maintain them; the wrecking balls began arriving in West Adams in force after the trauma of the Watts Riots, and the old Wagar house was among the casualties at St. James Park.